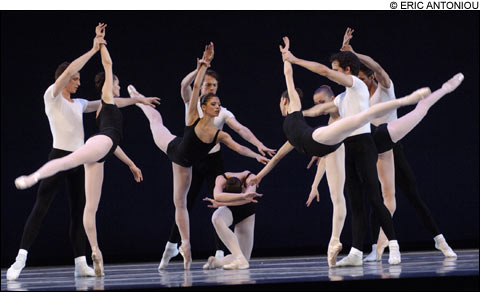

THE FOUR TEMPERAMENTS Kathleen Breen Combes (kneeling) brought off Choleric’s fast and eccentric steps. |

What’s on view at the Opera House through this weekend is dancing at its most demanding and imaginative. I don’t think I’ve ever seen The Four Temperaments (1946), Apollo (1928), and Theme and Variations (1947) together in one evening before. Singly, they pop up now and then, but seen in tandem, they deliver new discoveries about Balanchine and the dancers who embrace him.

Over his long, prolific career, Balanchine evoked many styles and moods. This program does show the neo-classicism of his Ballets Russes period (Apollo), an early example of his American modernism (Four T’s), and his wholehearted celebration of his roots in the Imperial Russian ballet (Theme and Variations). But, different as these three works are, seeing them together, you can recognize certain similarities — families of steps used and usages abandoned, touchstone compositional devices, attitudes to music, and ideas about how to present dancers, how to compose a ballet.

Four Temperaments is based on Paul Hindemith’s Theme with Four Variations, for string orchestra and piano, a piece Balanchine commissioned from the expatriate German composer. Hindemith wasn’t as daring as Stravinsky, but his music had a structural integrity that suited the choreographer wonderfully well. This score, and the ballet Balanchine made to it, is a marvelous exposition of three interrelated themes that begin very simply, sprout into diverse but linked designs, and come together in a grand formal conclusion.

Imagine the shock in 1946 when the curtain went up to reveal a man and a woman, just standing center stage, close together facing the audience, their arms twined in skater’s position, their legs in parallel. They extend their legs one at a time, flex, point, turn, gesture, pivot. But next, instead of being bolstered by other dancers, they leave, and two more couples appear one after the other, to demonstrate some of ballet’s other secrets — allegro, adagio — and some of Balanchine’s own — tilted supported swings, angular lifts, syncopated meters. And this is just the introduction.

I’ve written reams about Four Temperaments, and I could write more here, but space allows only a few remarks about the first two Boston Ballet performances last week. Each of the four sections (the four mediæval humors) features a soloist or solo couple and a small corps of women. None of the title temperaments is literally acted out. In the last movement, they gradually assemble till they make up a full ballet ensemble of 22: 14 corps women, the three introductory couples, and the five soloists.

Both John Lam and Jeffrey Cirio were good as Melancholic. In the technical fireworks of Sanguinic, Erica Cornejo looked her usual precise self, partnered by Nelson Madrigal; Rie Ichikawa wasn’t quite up to Sanguinic’s technical demands, but James Whiteside looked elegant. Jaime Diaz was excellent in the wavery bewilderments of Phlegmatic; Carlos Molina looked merely out of control. Choleric gets a very short solo before the group begins to assemble, but both Kathleen Breen Combes and Tiffany Hedman brought off its fast and eccentric steps.

Throughout this ballet, the corps has fascinating counterpoint rhythms to do, and strange floor patterns, like diagonal marches and circular pathways coming on and off pointe. One of Balanchine’s most important innovations was the way he brought the traditional corps de ballet out of the background by giving them hard steps and patterns to carry out — often in units so small that each person carries weight, gets noticed. In Four T’s, they acquire the added glamour of showgirls, with high kicks and tilted pelvises, hip-sidling walks, and fetching leg gestures.

The Saturday matinee brought a very fine cast to Apollo: Yury Yanowsky with Melissa Hough as Terpsichore, Cornejo as Calliope, and Misa Kuranaga as Polyhymnia. Pavel Gurevich, Lia Cirio, Rie Ichikawa, and Whitney Jensen opening night were less well-matched. Jensen is very young and rising. She dances with her eyes and doesn’t try to win us with a stuck-on smile.

In Four Temperaments, it was refreshing to see the whole company resist its unfortunate tendency to grin all the time. But in Theme and Variations, the corps reverted to this practice, which Balanchine made obsolete. Other than that, Theme was a great pleasure, especially on opening night, when it was led by Kuranaga and Whiteside. Saturday afternoon, Lia Cirio looked strong but stuck in a smile, whereas Molina just couldn’t meet the technical demands.

Theme and Variations was a neat complement to Four Temperaments, its near-contemporary in Balanchine’s canon. It, too, opens with basics, a demonstration of thematic steps by the principal couple, and proceeds to expand on them in miraculously varied ways. It, too, ends with a cumulative celebration — in this case, the 12 corps women are joined by male partners for the first time as Tchaikovsky’s music (the last movement from his Third Suite) ramps up into a final polonaise.

Theme is High Imperial classicism with all stops out. When the curtain goes up, we see the women posing in an expectant fourth position with the leading couple down front. The women wear Jens-Jacob Worsaae’s elegant tutus, white skirts with pale grey-blue bodices. The background is a blue cyclorama with white gauze drapes and a crystal chandelier. The audience goes “Ooooohhh!” and applauds.

After the ABCs — tendu, port de bras, révérence — the music leads into a string of numbers in different textures, and Balanchine obliges with his own inventions. My pulse rate spikes at the first notes of both allegro variations, anticipating the cascade of steps to come — academic figures and little jumps put together without stops in surprising order. Kuranaga is so in charge of the choreography, she can take her own playful delays and speed-ups against the musical baseline. In contrast, Whiteside’s expansive leaps, up and out and to the side, have a majestic effect. And the corps makes counterpoint filigree work in trios, and later the women form a chain that supports Kuranaga, who’s changing from one formal position to another while the chain simultaneously curls around and through itself.

Throughout this ballet, the corps has fascinating counterpoint rhythms to do, and strange floor patterns, like diagonal marches and circular pathways coming on and off pointe. One of Balanchine’s most important innovations was the way he brought the traditional corps de ballet out of the background by giving them hard steps and patterns to carry out — often in units so small that each person carries weight, gets noticed. In Four T’s, they acquire the added glamour of showgirls, with high kicks and tilted pelvises, hip-sidling walks, and fetching leg gestures.

The Saturday matinee brought a very fine cast to Apollo: Yury Yanowsky with Melissa Hough as Terpsichore, Cornejo as Calliope, and Misa Kuranaga as Polyhymnia. Pavel Gurevich, Lia Cirio, Rie Ichikawa, and Whitney Jensen opening night were less well-matched. Jensen is very young and rising. She dances with her eyes and doesn’t try to win us with a stuck-on smile.

In Four Temperaments, it was refreshing to see the whole company resist its unfortunate tendency to grin all the time. But in Theme and Variations, the corps reverted to this practice, which Balanchine made obsolete. Other than that, Theme was a great pleasure, especially on opening night, when it was led by Kuranaga and Whiteside. Saturday afternoon, Lia Cirio looked strong but stuck in a smile, whereas Molina just couldn’t meet the technical demands.

Theme and Variations was a neat complement to Four Temperaments, its near-contemporary in Balanchine’s canon. It, too, opens with basics, a demonstration of thematic steps by the principal couple, and proceeds to expand on them in miraculously varied ways. It, too, ends with a cumulative celebration — in this case, the 12 corps women are joined by male partners for the first time as Tchaikovsky’s music (the last movement from his Third Suite) ramps up into a final polonaise.

APOLLO: Dancers on holiday making up games on the beach. |

After the ABCs — tendu, port de bras, révérence — the music leads into a string of numbers in different textures, and Balanchine obliges with his own inventions. My pulse rate spikes at the first notes of both allegro variations, anticipating the cascade of steps to come — academic figures and little jumps put together without stops in surprising order. Kuranaga is so in charge of the choreography, she can take her own playful delays and speed-ups against the musical baseline. In contrast, Whiteside’s expansive leaps, up and out and to the side, have a majestic effect. And the corps makes counterpoint filigree work in trios, and later the women form a chain that supports Kuranaga, who’s changing from one formal position to another while the chain simultaneously curls around and through itself.

I haven’t said much about Apollo because it doesn’t activate my thrill centers as much as the other two ballets. Balanchine’s compositional tactics in the earlier work are less intricate, more soloistic. What he didn’t do — a young man’s deliberate contrariness, perhaps — was make it “Greek” in the diaphanous manner of Isadora Duncan, Michel Fokine, and innumerable other animators of ancient sculptures who preceded him. His Apollo and Muses are noble but human, dancers on holiday making up games on the beach.

I can’t quite assimilate the mystique of Apollo as Balanchine’s first major ballet and the icon of classical beauty. The ballet is hard to see against the æsthetic reverence that shrouds it, and the long line of great dancers who’ve relived it. I’ve seen Peter Martins, Mikhail Baryshnikov, and other gods in this role, and I don’t know how dancers are able to reimagine it now.

Former New York City Ballet dancer Ben Huys staged Apollo for Boston. The whole program received the invaluable coaching of Merrill Ashley on behalf of the Balanchine Trust, and the other assisting régisseurs were Sandra Jennings and Russell Kaiser. Unless you follow the company to Spain this summer, you won’t see these gems again after Sunday.

I can’t quite assimilate the mystique of Apollo as Balanchine’s first major ballet and the icon of classical beauty. The ballet is hard to see against the æsthetic reverence that shrouds it, and the long line of great dancers who’ve relived it. I’ve seen Peter Martins, Mikhail Baryshnikov, and other gods in this role, and I don’t know how dancers are able to reimagine it now.

Former New York City Ballet dancer Ben Huys staged Apollo for Boston. The whole program received the invaluable coaching of Merrill Ashley on behalf of the Balanchine Trust, and the other assisting régisseurs were Sandra Jennings and Russell Kaiser. Unless you follow the company to Spain this summer, you won’t see these gems again after Sunday.

No comments:

Post a Comment