An exhibition in Florence strives to present 1930s Italy as a cauldron of experimentation. Instead, it's a bleak journey into the aesthetic lifelessness of a totalitarian society

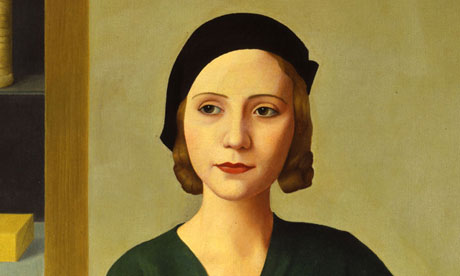

Flat white … Antonio

Donghi's Woman at the Cafe (1932), featured in Palazzo Strozzi's

exhibition The 30s: The Arts in Italy Beyond Fascism

Flat white … Antonio

Donghi's Woman at the Cafe (1932), featured in Palazzo Strozzi's

exhibition The 30s: The Arts in Italy Beyond Fascism

In 1938 Adolf Hitler arrived at Santa Maria Novella railway station in Florence to be greeted by red, white and black swastika banners, Italian fascist symbols, fake statues and choreographed crowds. He was taken by Benito Mussolini

through this beautiful city of the Italian Renaissance to admire its

masterpieces. Hitler saw himself as an artist. He had been to art

school. Now he communed with Michelangelo while the masses cheered his every step.

Six years later, in 1944, German troops retreating through Florence blew up all of its historic bridges except the fabled Ponte Vecchio and mined the medieval centre. Hitler's embrace was deadly.

It is deadly still. Susan Sontag once published an essay called Fascinating Fascism. I don't know about fascination, but the death-force of fascism, its murder of the human heart, grips a major exhibition in Florence that sets out to reveal the richness of the arts in 1930s Italy. This show slides inexorably into the poisonous cesspit of Europe's history.

Anni Trenta ("the 30s") at the Palazzo Strozzi explores the culture of Italy under the rule of Mussolini when he and Hitler seemed to many observers around the world to be the coming men of a new Europe. Democracy was discredited. The Depression seemed to have revealed basic flaws in free markets and elected governments, as the historian Mark Mazower shows in his profound book Dark Continent. It was the corporate states of fascism with their massive public projects that appeared to offer a way forward – unless you were on the left and looked to Stalin's Russia.

The most terrifying and best part of Anni Trenta is its side-exhibit about Hitler's visit to Florence. This captures the true monstrosity of the era. History is well told here. But does the art of the fascist era deserve to be reclaimed and enjoyed apolitically?

This is where the exhibition gets in trouble.

Its subtitle is "The Arts in Italy Beyond Fascism". It strives to present fascist Italy as a cauldron of creativity where rich experiments were taking place. It totally fails to make that case. In reality, this is a depressing, bleak journey through the art of a totalitarian state. The new Europe of fascism was a dead end. It bred heartless mediocrity. Paintings of strident men in front of mighty locomotives and chic women looking icily glamorous do not in the least challenge my assumptions – in fact they seem to be typical of what you might think fascists would hang in their galleries.

This show cannot make decadent futurists – their early brilliance long gone – or conservative neo-classicists any more vital than they were. What it does reveal, however, is how fascism used art to shape society in subtle ways. It appreciated the value of a busy, well-funded official art world. Italian fascism worked through what the communist thinker Antonio Gramsci – who died in 1937 after years in fascist prisons – called "hegemony": by spreading tentacles of involvement through civil society.

Where this exhibition succeeds is in revealing the fascist institutionalisation of art. We see paintings that won fascist Italy's Bergamo prize, and designs for public art. Art was a component of fascist society.

The result was a strange, lifeless aesthetic bubble where prizes were given and artists were promoted for works that were at best muted by fear, at worst glorying in mad delusion. "Fascism says, 'Long live art, let the world die,'" said the German communist Walter Benjamin at the time.

The art of Italy in the 1930s is an art of the dead. When Hitler was taken up San Miniato al Monte on his 1938 visit, he said he could finally understand his favourite painting, Arnold Böcklin's Isle of the Dead (which does in fact depict a cemetery on this hill overlooking Florence).

In a city of beauty, all he responded to was the allure of the grave.

Six years later, in 1944, German troops retreating through Florence blew up all of its historic bridges except the fabled Ponte Vecchio and mined the medieval centre. Hitler's embrace was deadly.

It is deadly still. Susan Sontag once published an essay called Fascinating Fascism. I don't know about fascination, but the death-force of fascism, its murder of the human heart, grips a major exhibition in Florence that sets out to reveal the richness of the arts in 1930s Italy. This show slides inexorably into the poisonous cesspit of Europe's history.

Anni Trenta ("the 30s") at the Palazzo Strozzi explores the culture of Italy under the rule of Mussolini when he and Hitler seemed to many observers around the world to be the coming men of a new Europe. Democracy was discredited. The Depression seemed to have revealed basic flaws in free markets and elected governments, as the historian Mark Mazower shows in his profound book Dark Continent. It was the corporate states of fascism with their massive public projects that appeared to offer a way forward – unless you were on the left and looked to Stalin's Russia.

The most terrifying and best part of Anni Trenta is its side-exhibit about Hitler's visit to Florence. This captures the true monstrosity of the era. History is well told here. But does the art of the fascist era deserve to be reclaimed and enjoyed apolitically?

This is where the exhibition gets in trouble.

Its subtitle is "The Arts in Italy Beyond Fascism". It strives to present fascist Italy as a cauldron of creativity where rich experiments were taking place. It totally fails to make that case. In reality, this is a depressing, bleak journey through the art of a totalitarian state. The new Europe of fascism was a dead end. It bred heartless mediocrity. Paintings of strident men in front of mighty locomotives and chic women looking icily glamorous do not in the least challenge my assumptions – in fact they seem to be typical of what you might think fascists would hang in their galleries.

This show cannot make decadent futurists – their early brilliance long gone – or conservative neo-classicists any more vital than they were. What it does reveal, however, is how fascism used art to shape society in subtle ways. It appreciated the value of a busy, well-funded official art world. Italian fascism worked through what the communist thinker Antonio Gramsci – who died in 1937 after years in fascist prisons – called "hegemony": by spreading tentacles of involvement through civil society.

Where this exhibition succeeds is in revealing the fascist institutionalisation of art. We see paintings that won fascist Italy's Bergamo prize, and designs for public art. Art was a component of fascist society.

The result was a strange, lifeless aesthetic bubble where prizes were given and artists were promoted for works that were at best muted by fear, at worst glorying in mad delusion. "Fascism says, 'Long live art, let the world die,'" said the German communist Walter Benjamin at the time.

The art of Italy in the 1930s is an art of the dead. When Hitler was taken up San Miniato al Monte on his 1938 visit, he said he could finally understand his favourite painting, Arnold Böcklin's Isle of the Dead (which does in fact depict a cemetery on this hill overlooking Florence).

In a city of beauty, all he responded to was the allure of the grave.

No comments:

Post a Comment