By transforming filthy lucre into art, rich American financiers such as Steven Cohen earn more prestige than any yacht could buy

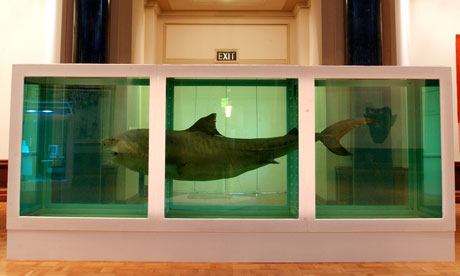

Something fishy ... Damien Hirst's The

Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living (1991).

Photograph: David Levene for the Guardian

Following on from yesterday's ruminations on art and money, it might be fun to look at the career of Steven Cohen, owner of Damien Hirst's shark, in more detail.

Cohen leapt up the ranks of contemporary art collectors not just because he bought this iconic work of the late 20th century, but because he arranged to lend it to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. I was amazed to accidentally come across The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living in this august museum. The timeworn leathery body of the tiger shark hung in its blue liquid near a window overlooking leafy Central Park.

In having his catch displayed in America's greatest art museum, Cohen achieved something even Charles Saatchi never has. So what makes Cohen so good at swimming in the waters of high culture? The answer may tell us something about how the art world works.

Cohen put some works from his art collection, then valued at £320m, on view at Sotheby's in New York in 2009. They were not for sale, and they exuded an aura of immense cultural – as well as economic – capital: no pickled sharks here, but paintings by Van Gogh, De Kooning and Picasso. As with his loan to the Met, he once again displayed a command of the heights of art.

In 2010 he gave an interview to Vanity Fair. In it, we learn that he lives in a mansion in Greenwich, Connecticut, and is America's 36th richest man. At the time, reported Vanity Fair, there were

These reports caught my eye when I was following up Cohen's art collecting, but regardless of such stories there is a bigger picture. Before the 2008 crash, hedge fund managers were often seen as modern geniuses, yet today they are more likely to be vilified as a symptom of the madness of modern finance. A hedge fund supposedly "hedges its bets" and protects its investors by playing the markets in such a way as to be protected against a downturn. But this apparently cautious image is far from how hedge funds evolved in the 1980s and 90s.

Adept and fast-moving gamblers – Cohen told Vanity Fair that student poker-playing was the inspiration for his career – were lauded in the credit-boom years as the new heroes of global finance for the innovative ways in which they made billions. Today, such non-traditional finance looks like part of a festering problem.

Is art, for a billionaire, just something to do with your money, or is it a way to turn wealth into more satisfying forms of power? By translating wealth into art and culture, art collectors give themselves a stature in society that a big yacht won't buy. The wealthy in America have been good at this for a long time, and their efforts to turn filthy lucre into civilised prestige have given that nation its great museums.

Cohen seems to be bidding to become a great American collector whose appetite for the new is enriched by a respect for art history. As such, he is on his way to a stately fame. Or is he? That entire model of capitalism – the one where it works – is shuddering and juddering, and many blame wacky financial inventions such as hedge funds for getting us into this mess. If the money machine breaks, so does the art machine, presumably. Or perhaps what breaks is our deference to the idea that money makes taste.

I feel a bit sick. I need to stop thinking about art and money now.

Cohen leapt up the ranks of contemporary art collectors not just because he bought this iconic work of the late 20th century, but because he arranged to lend it to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. I was amazed to accidentally come across The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living in this august museum. The timeworn leathery body of the tiger shark hung in its blue liquid near a window overlooking leafy Central Park.

In having his catch displayed in America's greatest art museum, Cohen achieved something even Charles Saatchi never has. So what makes Cohen so good at swimming in the waters of high culture? The answer may tell us something about how the art world works.

Cohen put some works from his art collection, then valued at £320m, on view at Sotheby's in New York in 2009. They were not for sale, and they exuded an aura of immense cultural – as well as economic – capital: no pickled sharks here, but paintings by Van Gogh, De Kooning and Picasso. As with his loan to the Met, he once again displayed a command of the heights of art.

In 2010 he gave an interview to Vanity Fair. In it, we learn that he lives in a mansion in Greenwich, Connecticut, and is America's 36th richest man. At the time, reported Vanity Fair, there were

persistent rumors that Cohen's fund, SAC Capital – one of the biggest movers of the stock market in the world; responsible, in better days, for as much as 3% of all trading on the New York Stock Exchange – is engaged in illegal information-gathering, rumors which have been stoked anew by a federal crackdown on another hedge fund, the Galleon Group, which employed several former SAC traders before collapsing.The rumours persist. This May, the Wall Street Journal reported that "prosecutors are examining trades made in an account overseen by hedge fund titan Steven Cohen that were suggested by two of his former fund managers who have pleaded guilty to insider trading".

These reports caught my eye when I was following up Cohen's art collecting, but regardless of such stories there is a bigger picture. Before the 2008 crash, hedge fund managers were often seen as modern geniuses, yet today they are more likely to be vilified as a symptom of the madness of modern finance. A hedge fund supposedly "hedges its bets" and protects its investors by playing the markets in such a way as to be protected against a downturn. But this apparently cautious image is far from how hedge funds evolved in the 1980s and 90s.

Adept and fast-moving gamblers – Cohen told Vanity Fair that student poker-playing was the inspiration for his career – were lauded in the credit-boom years as the new heroes of global finance for the innovative ways in which they made billions. Today, such non-traditional finance looks like part of a festering problem.

Is art, for a billionaire, just something to do with your money, or is it a way to turn wealth into more satisfying forms of power? By translating wealth into art and culture, art collectors give themselves a stature in society that a big yacht won't buy. The wealthy in America have been good at this for a long time, and their efforts to turn filthy lucre into civilised prestige have given that nation its great museums.

Cohen seems to be bidding to become a great American collector whose appetite for the new is enriched by a respect for art history. As such, he is on his way to a stately fame. Or is he? That entire model of capitalism – the one where it works – is shuddering and juddering, and many blame wacky financial inventions such as hedge funds for getting us into this mess. If the money machine breaks, so does the art machine, presumably. Or perhaps what breaks is our deference to the idea that money makes taste.

I feel a bit sick. I need to stop thinking about art and money now.

No comments:

Post a Comment